Amniotic Fluid Embolism is a life‑threatening obstetric emergency that occurs when amniotic fluid, fetal cells, or debris enter the maternal bloodstream, triggering a rapid cascade of cardiovascular collapse, respiratory failure, and coagulopathy. Though it affects roughly 1 in 40,000 births, the condition carries a mortality rate of up to 60% when not recognized instantly. Expectant mothers, partners, and clinicians all share a common job: spot the warning signs early enough to launch aggressive supportive care.

What Exactly Is Amniotic Fluid Embolism?

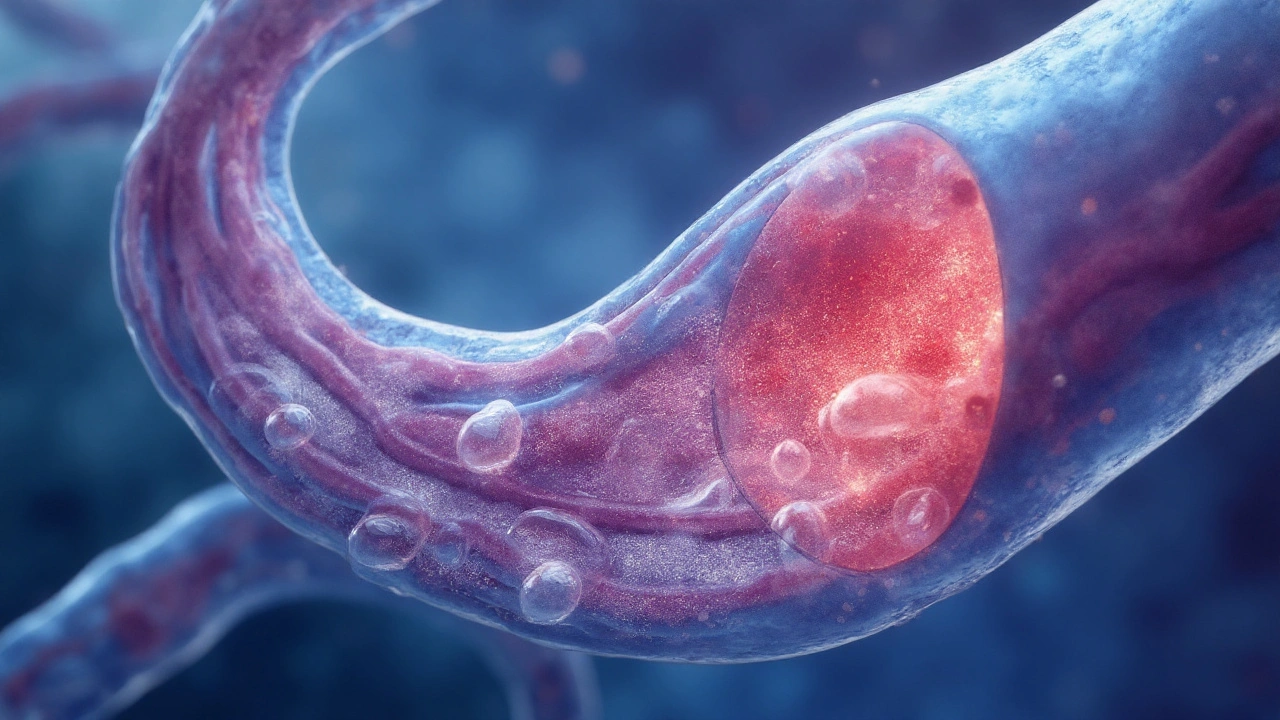

In plain terms, AFE is a sudden blockage of the maternal pulmonary circulation the network of vessels that carries blood from the heart to the lungs by a mixture of amniotic fluid, hair, vernix, and other fetal material. The body reacts as if it were a severe allergic reaction, releasing massive amounts of inflammatory mediators that cause the heart to fail, the lungs to flood, and the blood to clot throughout the body.

How Does It Happen? The Pathophysiology

- Rupture of uterine vessels - during labor, cesarean section, or even a traumatic delivery, the uterine wall can tear, opening a gateway for fluid to breach the maternal blood pool.

- Entry of fetal debris - amniotic fluid carries cells, meconium, and lanugo that act as foreign antigens.

- Immune cascade - once in the bloodstream, these particles trigger an anaphylactoid response, releasing histamine, tryptase, and cytokines.

- Cardiopulmonary collapse - the sudden rise in pulmonary artery pressure stalls right‑ventricular output, leading to severe hypotension.

- Coagulopathy - the same inflammatory surge activates the clotting cascade, often resulting in disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), a form of coagulopathy widespread clotting that paradoxically causes severe bleeding.

Who Is at Risk?

While anyone can develop AFE, research highlights a handful of risk factors that raise the odds:

- Advanced maternal age (over 35years)

- Multiple gestation (twins, triplets)

- Labor induction or augmentation with oxytocin

- Placental abnormalities such as placenta previa or abruption

- Cesarean delivery, especially emergency procedures

Understanding these cues allows emergency obstetric care the rapid, multidisciplinary response to life‑threatening pregnancy complications teams to keep a higher index of suspicion.

What Does It Look Like? Clinical Presentation

The classic AFE picture unfolds in seconds to minutes, often during the first stage of labor, delivery, or shortly after birth. The hallmark triad includes:

- Sudden shortness of breath - a feeling of not getting enough air, often accompanied by a gasp.

- Cardiovascular collapse - rapid drop in blood pressure, loss of pulse, or cardiac arrest.

- Coagulopathy - unexpected bleeding from the uterus, IV sites, or mucous membranes.

Other red‑flag signs are cyanosis, seizures, and a feeling of impending doom reported by the mother. Because many of these symptoms overlap with pulmonary embolism, severe allergic reaction, or hemorrhagic shock, clinicians must act fast and assume AFE until proven otherwise.

Diagnosing AFE: When Time Is Not on Your Side

There is no single lab test that confirms AFE. Diagnosis rests on a combination of clinical judgment and exclusion of other emergencies. Typical steps include:

- Continuous cardiac monitoring - looking for sudden arrhythmias or asystole.

- Arterial blood gases - often reveal severe hypoxia (PaO₂<60mmHg) and metabolic acidosis.

- Coagulation profile - a rapid drop in fibrinogen (<150mg/dL) and a spike in D‑dimer levels point toward DIC.

- Echocardiography - may show right‑ventricular overload, a hallmark of pulmonary blockage.

- Post‑mortem histology (rare) - presence of fetal squamous cells in maternal pulmonary vessels.

Given the rapid progression, treatment should start before a definitive diagnosis is nailed down.

Managing the Crisis: Immediate Treatment Steps

Effective AFE response hinges on three pillars: airway, circulation, and coagulation. A typical algorithm looks like this:

- Airway &breathing - Intubate instantly, deliver 100% oxygen, and consider high‑frequency ventilation if oxygenation remains poor.

- Circulatory support - Administer large‑volume crystalloid boluses, followed by vasopressors (e.g., norepinephrine) to maintain MAP>65mmHg. If cardiac arrest occurs, follow standard ACLS protocols, but be ready for reversible causes like hypoxia.

- Control coagulopathy - Transfuse fresh frozen plasma, platelets, and cryoprecipitate to keep fibrinogen>150mg/dL. In extreme cases, consider recombinant factor VIIa under hematology guidance.

- Advanced support - For refractory hypoxemia, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) can buy time. Some tertiary centers report survival rates exceeding 80% with early ECMO.

- Uterine management - Perform a rapid uterine evacuation (manual or surgical) to reduce ongoing exposure to amniotic fluid.

All interventions should happen in a dedicated obstetric ICU, where a multidisciplinary team obstetricians, anesthetists, intensivists, and blood bank staff can coordinate care.

Outcomes, Prognosis, and Prevention

Survival depends on how quickly the team recognizes AFE and launches aggressive support. Recent data from the RCOG and ACOG registries show a decline in mortality from 70% in the 1990s to roughly 35% today, largely thanks to better resuscitation protocols and early ECMO use.

Preventive measures focus on minimizing known triggers:

- Avoid unnecessary labor induction; use evidence‑based criteria.

- Employ gentle assisted delivery techniques to reduce uterine trauma.

- Maintain a high index of suspicion in high‑risk pregnancies (multiple gestation, placenta previa).

- Ensure rapid availability of massive transfusion protocols and ECMO capabilities at tertiary centers.

While AFE cannot be eliminated entirely, these steps dramatically lower the odds of a catastrophic event.

Related Concepts and Broader Context

Understanding AFE also helps make sense of other obstetric emergencies:

- Placental abruption - premature separation of the placenta that can also cause massive bleeding and shock.

- Severe postpartum hemorrhage - shares the need for massive transfusion and rapid uterine evacuation.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE) - a clot that blocks the pulmonary artery; unlike AFE, PE originates from deep‑vein thrombosis rather than fetal debris.

- Maternal mortality - AFE remains a leading cause of death in high‑income countries despite overall declines in maternal mortality.

These connections illustrate why a robust maternal health system the network of prenatal, perinatal, and postpartum services must address all of them collectively.

Next Steps for Expectant Mothers and Clinicians

If you’re pregnant and concerned about AFE:

- Discuss any risk factors with your obstetrician during prenatal visits.

- Ask about the hospital’s emergency obstetric protocols - do they have a massive transfusion plan?

- Consider delivering at a facility with an on‑site ICU and, if possible, ECMO capability.

For healthcare providers, consider adding AFE drills to your obstetric emergency training. Simulation scenarios that run through airway, circulatory, and coagulation management improve team performance and, ultimately, patient survival.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the first signs of amniotic fluid embolism?

The earliest clues are sudden shortness of breath, a rapid drop in blood pressure, and unexplained bleeding. These symptoms can appear within minutes of labor or delivery and require immediate emergency response.

How is AFE different from a regular pulmonary embolism?

A regular pulmonary embolism is caused by a blood clot that travels from the legs or pelvis to block the lung arteries. AFE involves fetal material entering the mother’s bloodstream, triggering an anaphylactoid reaction and often leading to severe coagulopathy, which is not typical in standard PE.

Can amniotic fluid embolism be prevented?

Complete prevention isn’t possible, but risk can be lowered by avoiding unnecessary inductions, handling the uterus gently during delivery, and ensuring rapid access to massive transfusion and ECMO at tertiary centers.

What is the survival rate for mothers who experience AFE?

Modern studies report a survival rate of about 40‑45% when AFE is recognized and treated promptly. Outcomes improve dramatically with early aggressive support and, in some cases, ECMO.

Should I be worried about AFE if I have a low‑risk pregnancy?

The absolute risk remains low-about 1 in 40,000 births-so most low‑risk pregnancies will never encounter it. However, being informed about the signs can help you and your care team act quickly if it does occur.

Ernie Rogers

September 21, 2025 AT 23:38Just read through that AFE rundown and I gotta say the US should invest more in obstetric emergency training we got the tech but not always the troops on the ground its a real shame when lives are lost because of slow response

Eunice Suess

September 24, 2025 AT 07:13This article really hits the heart It’s terrifying how quickly a normal labor can flip into a nightmare but the facts are clear and we need to spread the word so no mom feels alone

Anoop Choradia

September 26, 2025 AT 14:48One must consider that the current discourse surrounding amniotic fluid embolism is awash with superficial statistics while deeper etiological mechanisms remain obfuscated by institutional complacency. The literature frequently cites a mortality of up to sixty percent yet fails to interrogate the sociopolitical determinants that influence access to advanced therapies such as ECMO. Moreover, the alleged rarity of the condition, noted as one in forty thousand, may be a byproduct of under‑reporting in low‑resource settings, thereby skewing global epidemiological models. It is also noteworthy that many obstetric units lack standardized massive transfusion protocols, a gap that appears to be deliberately ignored by governing bodies seeking to minimize perceived systemic failures. The paradigm that AFE represents a purely physiologic catastrophe neglects the fact that iatrogenic interventions-particularly unnecessary labor inductions-serve as catalysts for these events. Consequently, the push for “evidence‑based induction criteria” should be amplified, not merely mentioned in passing. There exists a discernible pattern of data suppression wherein the correlation between aggressive oxytocin administration and heightened AFE risk is downplayed. In addition, the emergence of ECMO capabilities in tertiary centers is lauded, yet the equitable distribution of such resources remains elusive, raising concerns about a two‑tiered system of care. The prevailing narrative also omits the potential role of environmental pollutants in modulating maternal immune responses, a hypothesis that warrants rigorous investigation. The interplay between maternal age, multiple gestations, and placental abnormalities is presented as a list of risk factors without contextualizing the underlying genetic predispositions that may amplify susceptibility. Finally, the absence of a definitive diagnostic biomarker perpetuates reliance on clinical gestalt, a practice that is vulnerable to bias and misinterpretation. In summation, while the article outlines contemporary management strategies, it insufficiently addresses the structural inequities and concealed variables that shape outcomes in amniotic fluid embolism.

bhavani pitta

September 28, 2025 AT 22:23While the piece enumerates standard risk factors, one could argue that the emphasis on advanced interventions eclipses the need for basic obstetric vigilance, especially in low‑resource environments.

Brenda Taylor

October 1, 2025 AT 05:58Seriously, ignoring the moral duty to have blood banks ready is just unacceptable 😠

virginia sancho

October 3, 2025 AT 13:33Hey there, just a heads up – if u ever need a quick refresher on AFE signs, keep a checklist on your phone. I always miss a beat when I’m sleep‑deprived so a simple bullet list helps a lot.

Also, talk to your OB about their emergency protocols early in pregnancy – it saves stress later.

Namit Kumar

October 5, 2025 AT 21:08Our nation’s hospitals must prioritize rapid ECMO deployment – every minute counts! 😉

Sam Rail

October 8, 2025 AT 04:43Cool article but honestly, most places just don’t have the gear – tough reality.

Taryn Thompson

October 10, 2025 AT 12:18From a clinical perspective, early recognition of the triad-sudden dyspnea, hypotension, and coagulopathy-remains the cornerstone of management. I would add that point‑of‑care ultrasound can be invaluable for assessing right‑ventricular strain in the acute setting. In addition, establishing a massive transfusion protocol ahead of time streamlines the process, reducing decision‑making delays. Finally, interdisciplinary drills that include obstetrics, anesthesiology, and critical care teams improve coordination during an actual event.

Lisa Lower

October 12, 2025 AT 19:53The reality of amniotic fluid embolism is that it can strike without warning and turn a joyous birth into a medical crisis in an instant.

First, the physiological cascade begins when fetal debris enters the maternal circulation, acting like a foreign invader that the body’s immune system cannot tolerate.

Second, the sudden release of inflammatory mediators causes the pulmonary vessels to constrict dramatically, leading to a rapid rise in pulmonary artery pressure.

Third, the heart struggles to pump against this resistance, resulting in right‑ventricular failure and systemic hypotension.

Fourth, the coagulation system is paradoxically activated, producing disseminated intravascular coagulation that can cause severe bleeding even as clots form in the microvasculature.

Fifth, the patient may experience a feeling of suffocation, cyanosis, and a terrifying sense of impending doom.

Sixth, immediate resuscitation efforts must focus on securing the airway, providing 100% oxygen, and establishing invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

Seventh, aggressive fluid resuscitation combined with vasopressors can help maintain perfusion while the underlying cause is addressed.

Eighth, rapid transfusion of packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and platelets is essential to counteract coagulopathy.

Ninth, if the facility has ECMO capability, early initiation can bridge the patient through refractory hypoxemia and circulatory collapse.

Tenth, a swift uterine evacuation-whether manual or surgical-reduces ongoing exposure to amniotic fluid and may improve maternal outcomes.

Eleventh, multidisciplinary teamwork, including obstetricians, anesthesiologists, intensivists, and blood bank personnel, is critical for coordinated care.

Twelfth, simulation drills that rehearse these steps have been shown to decrease response times and improve survival rates.

Thirteenth, post‑event debriefings help identify system gaps and reinforce best practices for future cases.

Fourteenth, ongoing research into biomarkers for early detection may someday allow us to intervene before the full syndrome unfolds.

Fifteenth, education of expectant mothers about warning signs empowers them to alert providers promptly, potentially saving lives.

In summary, while amniotic fluid embolism remains a rare and terrifying emergency, understanding its pathophysiology and implementing rapid, coordinated interventions can markedly improve outcomes.

Dana Sellers

October 15, 2025 AT 03:28We must hold hospitals accountable for lacking proper emergency protocols.

Damon Farnham

October 17, 2025 AT 11:03Indeed, the confluence of immunologic upheaval and hemodynamic collapse constitutes a formidable clinical challenge; nevertheless, the paucity of universally accepted diagnostic criteria perpetuates ambiguity, thereby compromising timely intervention; consequently, a paradigm shift toward standardized, evidence‑based protocols is imperative.

Gary Tynes

October 19, 2025 AT 18:38Yo, just keep calm and follow the checklist, it works every time. Dont forget to ask the doc about ECMO options.

Marsha Saminathan

October 22, 2025 AT 02:13Picture this: a mother in labor, the room buzzing, and suddenly the air feels like it’s been ripped away – that’s the nightmare of amniotic fluid embolism, and it’s not just a medical term, it’s a pulse‑pounding reality that can strike any expectant mother.

When the fetal debris sneaks into the bloodstream, it triggers a cascade that’s as wild as a fireworks show gone rogue, and the lungs gasp for air while the heart screams for help.

The sudden drop in blood pressure feels like a roller‑coaster plunge, and the clotting system goes berserk, making you bleed from places you never imagined.

What’s crazy is how fast it all happens – minutes, not hours – and the classic triad of breathlessness, collapsing blood pressure, and bleeding is your alarm bell.

Now imagine trying to juggle a massive transfusion, calling for ECMO, and performing a rapid uterine evacuation all at once – it’s a high‑stakes ballet that requires a rock‑solid team.

That’s why every hospital, even the ones tucked away in quiet towns, needs a massive‑transfusion protocol on standby, because waiting for supplies is a luxury you can’t afford.

And yes, the best defense is early recognition, so keep that checklist on your phone, and don’t be shy about asking your OB about the emergency plan – knowledge is power.

Even if you’re not a medical professional, knowing the signs can turn that split‑second panic into decisive action, and that can literally save a life.

So, spread the word, stay vigilant, and let’s make sure no mother faces this nightmare alone.

Justin Park

October 24, 2025 AT 09:48Life is fragile, and every heartbeat is a reminder of the marvel and mystery of existence 🌟

When a rare event like AFE strikes, it forces us to confront the limits of our knowledge and the depth of our compassion 🩺

Consider the paradox: a tiny fragment of the unborn child becomes a catalyst for the mother’s crisis, reflecting the interwoven nature of life itself.

What if we could anticipate it sooner? The pursuit of biomarkers is a quest for foresight in a world where time is often our enemy.

And yet, preparation – drills, protocols, teamwork – is our most reliable shield against the unexpected.

Let’s honor the resilience of those who survive and the dedication of the clinicians who fight on the front lines 🙏

Herman Rochelle

October 26, 2025 AT 16:23Just a reminder: keep your obstetric care team informed about your birth plan and any known risk factors, and don’t hesitate to ask about the hospital’s emergency response protocol.

Stanley Platt

October 28, 2025 AT 23:58In consideration of the aforementioned discourse, it is incumbent upon healthcare institutions to adopt a comprehensive, evidence‑based framework for the identification and management of amniotic fluid embolism; such protocols must be regularly reviewed, meticulously documented, and universally disseminated among all obstetric care providers.