When your skin breaks out in thick, red, scaly patches, it’s easy to think it’s just a cosmetic issue. But if those patches come with stiff, swollen fingers, achy heels, or lower back pain, you’re not just dealing with a skin condition-you’re dealing with psoriatic arthritis. This isn’t two separate problems. It’s one autoimmune disease showing up in two places: your skin and your joints.

What Exactly Is Psoriatic Arthritis?

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) happens when your immune system turns on your own body. It doesn’t just attack skin cells like in plain psoriasis-it also targets the lining of your joints, tendons, and even where ligaments attach to bone. The result? Pain, swelling, and eventually, joint damage if left unchecked. About 30% of people with psoriasis will develop PsA. For most, the skin comes first-about 85% of cases start with psoriasis years before joint pain shows up. But in 5 to 10% of cases, the joints hurt before the skin ever breaks out. That’s why doctors don’t wait for visible scales to make a diagnosis. If you have unexplained joint swelling, especially in your fingers or toes, and a family history of psoriasis, you need to be checked.The Classic Signs: More Than Just Red Skin and Aching Joints

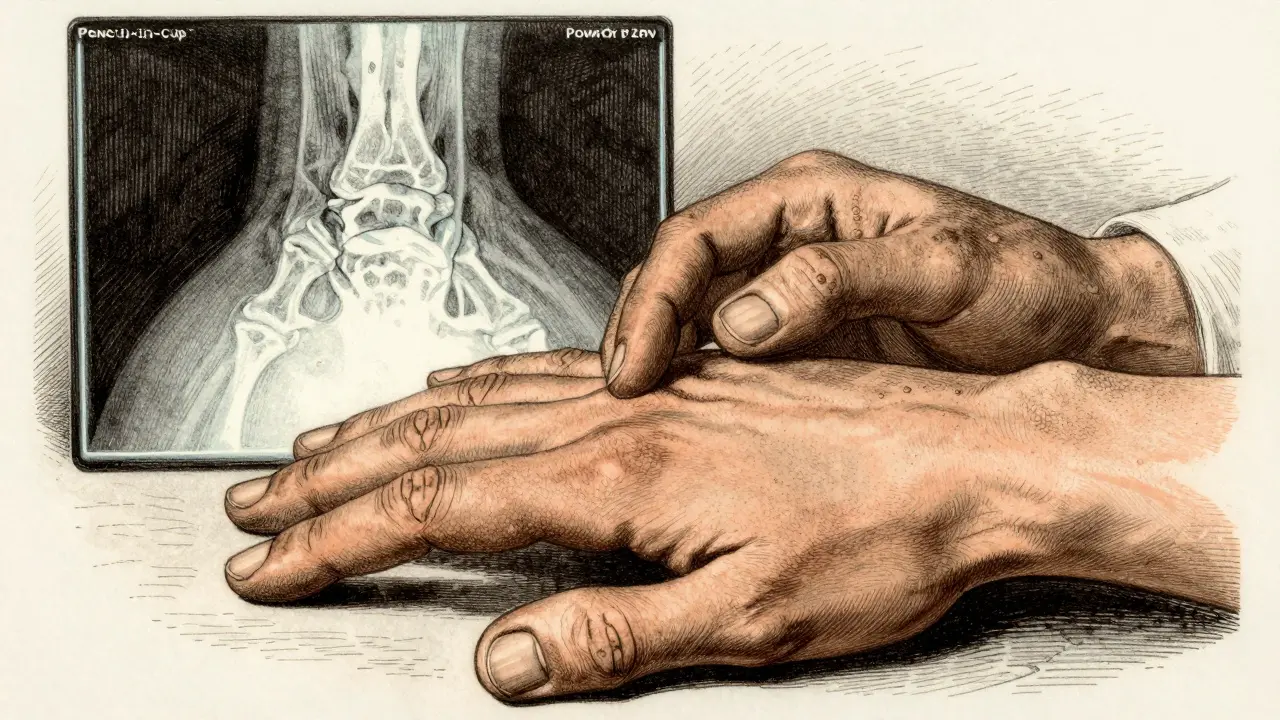

PsA doesn’t present like rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis. It has its own fingerprint.- Dactylitis: Entire fingers or toes swell up like sausages. This happens in about 40% of people with PsA and is a major red flag.

- Enthesitis: Pain where tendons or ligaments meet bone. Think of the back of your heel (Achilles tendon) or the bottom of your foot. Walking feels like stepping on glass.

- Nail changes: Pitting, thickening, or nails lifting off the nail bed. Up to 80% of PsA patients have this-more than half of all nail problems in adults are linked to PsA.

- Spinal involvement: Lower back pain that’s worse in the morning and improves with movement. It’s not just aging-it’s inflammation in the spine.

- Skin plaques: Thick, red patches with silvery scales. These aren’t just itchy-they’re inflamed from the inside out.

How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

There’s no single blood test for PsA. Diagnosis relies on connecting the dots using the CASPAR criteria, developed in 2006 and still the gold standard today. To get a confirmed diagnosis, you need:- Current or past psoriasis (3 points)

- Psoriatic nail changes (1 point)

- Negative rheumatoid factor (1 point)

- Dactylitis or typical joint damage on X-ray (1 point)

- Family history of psoriasis (1 point)

What Causes It? Genetics, Immunity, and Environment

You don’t catch PsA like a cold. It’s not contagious. But you can inherit the risk. Specific genes-especially HLA-B27, HLA-B38, and HLA-B39-make you more likely to develop it. If a close relative has psoriasis or PsA, your risk goes up. But genes alone don’t cause it. Something has to trigger it. Stress, infections (like strep throat), injury, or even certain medications can flip the switch. Recent research points to your gut. Studies show PsA patients have different gut bacteria than healthy people. This “gut-skin-joint axis” might explain why some people see improvement when they change their diet or take probiotics. The immune system goes haywire, overproducing inflammatory chemicals like TNF-alpha, IL-17, and IL-23. These are the exact targets of today’s most effective treatments.

Treatment: Stopping the Damage Before It Starts

The goal isn’t just to feel better-it’s to stop joint damage before it’s permanent. That’s why early treatment matters.- NSAIDs (like ibuprofen or naproxen) help with mild pain and swelling but don’t stop disease progression.

- Methotrexate, a traditional DMARD, is often used for moderate cases. It’s affordable but slower to work.

- Biologics are the game-changers. These are injectable or IV drugs that block specific inflammatory proteins:

- TNF inhibitors (adalimumab, etanercept): Best for spine and tendon pain.

- IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab, ixekizumab): Best for skin plaques and nail changes.

- IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab, risankizumab): Newer, highly effective for both skin and joints.

What Does “Success” Look Like?

Doctors don’t just measure pain. They use Minimal Disease Activity (MDA) as the target. That means:- Tender joints: 1 or fewer

- Swollen joints: 1 or fewer

- Skin involvement: 1% or less of body surface

- Pain score: 15mm or less on a 100mm scale

- Global health score: 20mm or less

- Physical function (HAQ): 0.5 or lower

- No fatigue

The Hidden Risks: Comorbidities You Can’t Ignore

PsA isn’t just about skin and joints. It’s a systemic disease that increases your risk for other serious conditions.- Heart disease: 40-50% of PsA patients have metabolic syndrome. Your risk of heart attack is 43% higher than someone without PsA.

- Depression and anxiety: 1 in 3 people with PsA experience these. Chronic pain, visible skin changes, and fatigue take a mental toll.

- Diabetes and fatty liver: Linked to the same inflammation driving PsA.

- Early death: People with PsA have a 30-50% higher risk of dying prematurely-mostly from heart problems.

What’s Next? The Future of PsA Care

The next five years will change how PsA is managed.- Early detection: New imaging tools can spot inflammation in joints before you even feel pain.

- Biomarkers: Blood tests for calprotectin and MMP-3 may soon predict who will respond to which drug.

- Personalized treatment: Instead of trial and error, doctors will match you to the right drug based on your genes, symptoms, and blood markers.

- Prevention: Research is exploring whether fixing gut health or reducing stress early can delay or prevent PsA in high-risk people.

What Should You Do If You Suspect PsA?

If you have psoriasis and notice:- Swollen fingers or toes

- Stiffness that lasts more than 30 minutes in the morning

- Heel or sole pain without injury

- Nail changes you’ve never had before

Can psoriasis turn into psoriatic arthritis?

Psoriasis doesn’t "turn into" psoriatic arthritis-they’re two parts of the same autoimmune disease. About 30% of people with psoriasis will develop joint symptoms, but not everyone does. Having psoriasis increases your risk, but it doesn’t guarantee PsA will follow. The key is watching for signs like joint swelling, stiffness, or nail changes and getting checked early.

Is psoriatic arthritis the same as rheumatoid arthritis?

No. While both cause joint pain and swelling, rheumatoid arthritis (RA) usually affects the same joints on both sides of the body symmetrically and is linked to a positive rheumatoid factor blood test. Psoriatic arthritis often affects joints unevenly, causes dactylitis (sausage fingers), enthesitis (tendon pain), and is tied to psoriasis and negative rheumatoid factor. The treatments overlap but aren’t identical-some RA drugs don’t work for PsA.

Can diet or lifestyle changes help psoriatic arthritis?

Yes, but not as a replacement for medical treatment. Losing weight reduces stress on joints and lowers inflammation. Cutting back on sugar, processed foods, and alcohol can help. Some people report improvements with omega-3s, vitamin D, or Mediterranean diets. Gut health is also being studied-probiotics and fiber may reduce flare-ups. But diet alone won’t stop joint damage. It works best alongside medication.

Do biologics cure psoriatic arthritis?

No, biologics don’t cure PsA. But they can put it into long-term remission. Many people achieve minimal disease activity and stop progressing. Some can reduce or even stop medication after years of stable control, but most need ongoing treatment. Stopping too soon often leads to flare-ups. Think of biologics like insulin for diabetes-they manage the disease, not erase it.

How quickly should treatment start after diagnosis?

As soon as possible. Studies show that starting biologics within the first 2 years of joint symptoms significantly reduces the risk of permanent joint damage. Waiting even 6-12 months can lead to irreversible changes visible on X-rays. Early treatment doesn’t just relieve pain-it protects your future mobility.

kenneth pillet

January 16, 2026 AT 12:24Still tired though.

Jodi Harding

January 17, 2026 AT 18:41Danny Gray

January 19, 2026 AT 14:07Tyler Myers

January 19, 2026 AT 23:37Zoe Brooks

January 21, 2026 AT 13:31Kristin Dailey

January 22, 2026 AT 06:25Wendy Claughton

January 22, 2026 AT 11:30Also-please, if you’re reading this and you’re struggling… you’re not alone. I’ve been there. We’re in this together.

Stacey Marsengill

January 23, 2026 AT 20:50Aysha Siera

January 24, 2026 AT 15:59rachel bellet

January 26, 2026 AT 11:58