Pterygium is more than just a pink bump on the white of your eye. For people who spend a lot of time outdoors-surfers, farmers, construction workers, or even weekend gardeners-it’s a real problem. This growth starts on the conjunctiva, the clear tissue covering the white part of your eye, and slowly creeps onto the cornea, the clear front surface that helps focus light. When it gets big enough, it can blur your vision, make your eye feel gritty, and even change the shape of your cornea enough to cause astigmatism. In Australia, where UV levels are among the highest in the world, about 1 in 8 men over 60 have it. And it’s not rare-globally, 15 million people are diagnosed every year.

Why the Sun Is the Main Culprit

It’s not aging. It’s not genetics alone. It’s the sun. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the single biggest risk factor for pterygium. Studies show people living within 30 degrees of the equator have more than double the risk compared to those farther north or south. In Melbourne, even on cloudy days, UV levels can hit 8 or higher in summer. That’s enough to damage the delicate surface of your eye over time.Research from the University of Melbourne found that people with cumulative UV exposure above 15,000 joules per square meter had a 78% higher chance of developing pterygium. That’s roughly 200 days a year in tropical zones where the UV index exceeds 3.0-something that happens almost daily in Australia during spring and summer. The growth usually starts on the side of the eye closest to the nose, because that’s where sunlight reflects off the cheekbone and hits the eye at a sharp angle.

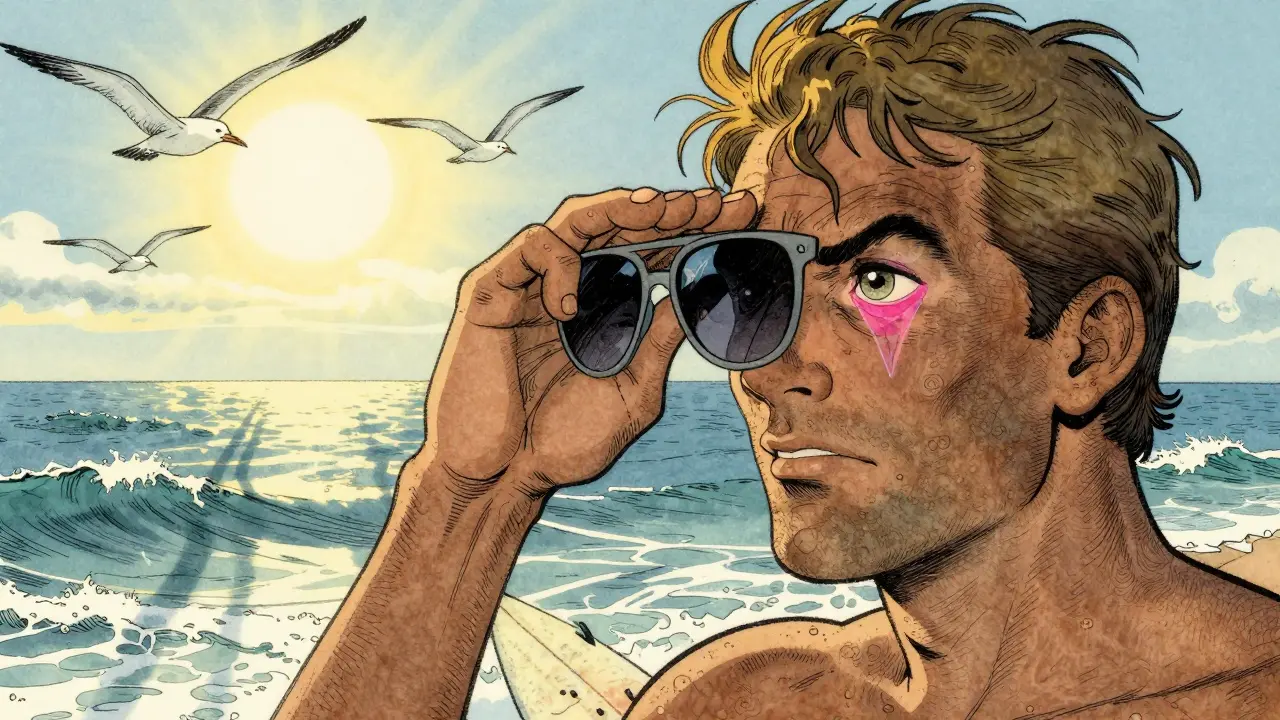

It’s not just direct sunlight. Reflection from water, sand, snow, and even concrete can bounce UV rays into your eyes. Surfers, fishermen, and skiers are especially at risk. One Reddit user, ‘SurfDude23,’ said after 15 years of surfing without sunglasses, he developed pterygium in both eyes. His contact lenses became unbearable, and his vision started blurring when the growth reached his pupil.

How to Tell It’s Pterygium-Not Just Dry Eyes

Many people mistake pterygium for dry eyes or pink eye. But there are clear signs:- A triangular, fleshy growth on the white of the eye, usually starting near the nose

- Visible blood vessels running through it

- Redness, irritation, or a gritty feeling that doesn’t go away with drops

- Blurred vision if the growth moves past the edge of the pupil

A doctor can confirm it with a simple slit-lamp exam-a bright light with a magnifying lens. No blood tests or scans are needed. The growth is usually 1 to 5 millimeters wide at the base when first noticed. Some stay small for years. Others grow fast-up to 2 millimeters a year-if you keep exposing your eyes to UV without protection.

It’s important to distinguish pterygium from pinguecula, which looks similar but stays on the conjunctiva and never reaches the cornea. Pinguecula is more common-about 70% of outdoor workers in tropical areas have it-but it rarely affects vision. Pterygium is the one that does.

When Surgery Becomes Necessary

Most small pterygia don’t need surgery. If it’s not bothering you, your doctor might just recommend UV-blocking sunglasses and lubricating drops. But surgery is the only way to remove it if:- Your vision is blurry or distorted

- You can’t wear contact lenses because of irritation

- The growth is cosmetically bothersome

- It’s growing quickly or causing chronic redness

The procedure usually takes less than an hour and is done under local anesthesia. You’re awake but feel no pain. The surgeon removes the abnormal tissue and then covers the area to prevent regrowth. There are three main techniques:

- Simple excision-just cutting it out. Cheap and quick, but recurrence rates are high-30% to 40%.

- Conjunctival autograft-taking a small piece of healthy conjunctiva from another part of your eye and stitching it over the area. This is now the gold standard. Recurrence drops to just 8.7%.

- Mitomycin C application-a chemo drug applied during surgery to kill off cells that cause regrowth. Used with autografts, it cuts recurrence to 5-10%.

Since 2023, the European Society of Cataract & Refractive Surgeons has started recommending amniotic membrane transplantation for recurrent cases, with success rates hitting 92% in multi-center trials.

What Recovery Is Really Like

People often think surgery means a long recovery. It’s not that bad-but it’s not painless, either.Most patients report:

- Redness and swelling for the first week

- Discomfort like having sand in the eye for 10-14 days

- Need to use steroid and antibiotic eye drops for 4-6 weeks

- Full healing takes 4-8 weeks

One patient on RealSelf.com said: “The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected.”

Side effects are rare but include infection, scarring, or temporary double vision. About 32% of patients report regrowth within 18 months if they don’t use adjunctive treatments like mitomycin C or autografts. That’s why follow-up appointments matter-your eye needs monitoring for at least a year after surgery.

Prevention: The Real Game-Changer

The best surgery is the one you never need. And prevention works.Wearing UV-blocking sunglasses every day outside cuts your risk dramatically. Look for lenses labeled “UV400” or that block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays, as required by ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards. Wraparound styles are best-they block light from the sides.

A wide-brimmed hat adds another 50% protection. One Reddit user, ‘OutdoorPhotog,’ said wearing sunglasses daily stopped his early-stage pterygium from growing. His last two eye exams showed no change.

Even in winter or on cloudy days, UV radiation is still present. In Melbourne, UV levels above 3 happen more than 200 days a year. That’s not just summer-it’s spring, fall, and even some winter days.

There’s no such thing as “just a little sun.” If you’re outside for more than 15 minutes, your eyes need protection. Kids aren’t immune either-sun damage builds up over decades.

What’s New in Treatment

The field is evolving fast. In March 2023, the FDA approved OcuGel Plus, a preservative-free lubricant specifically designed for post-surgery patients. In trials, it gave 32% more relief than standard artificial tears.Researchers are now testing topical rapamycin-a drug used in organ transplants-to stop the growth cells from multiplying. Early Phase II trials (NCT05214387) showed a 67% drop in recurrence at 12 months compared to placebo.

Laser-assisted removal is coming too. By 2027, 78% of ophthalmologists expect to use it. It’s not yet standard, but it promises faster healing and less tissue damage.

Still, access remains unequal. In rural areas of developing countries, only 12% of people can get surgery. In cities in Australia or the U.S., it’s 89%. That gap needs to close.

Bottom Line: Protect Your Eyes, Act Early

Pterygium isn’t cancer. It’s not an emergency. But left alone, it can steal your vision. The good news? You can stop it in its tracks.If you’re outside a lot, wear sunglasses every day-even if it’s cloudy. Get your eyes checked yearly, especially if you’re over 40. If you notice a pink, growing bump near your nose, don’t wait. See an eye doctor. Surgery is safe, effective, and often life-changing-if you catch it before it reaches your pupil.

And if you’ve had surgery? Keep wearing those sunglasses. The sun doesn’t take a day off-and neither should your protection.

Tim Goodfellow

December 21, 2025 AT 10:47Man, I never realized how brutal UV exposure is on the eyes until I moved from London to the Outback. My mate Alex here says it’s like sandpaper on your cornea over time. I used to think sunglasses were for fashion-now I wear them even when it’s overcast. That stat about 200+ days a year with UV above 3 in Melbourne? Chilling. And no, clouds don’t save you. They’re just polite liars.

Adrienne Dagg

December 22, 2025 AT 12:07So basically if you don’t wear sunglasses you’re just asking for a third eye? 😅 I got mine after a week in Bali and now I’m obsessed with UV400. My hat game is strong too. 🧢😎

Sajith Shams

December 23, 2025 AT 00:34You people are obsessed with Western medicine. In rural India, we’ve used cold compresses with neem leaf infusion for generations. It reduces inflammation and slows growth. No surgery needed. But of course, you’d rather pay $5k for a scalpel than try natural remedies. Profit-driven healthcare at its finest.

Ryan van Leent

December 24, 2025 AT 17:54Ive been surfing since I was 12 and never wore shades till I was 35 now I got pterygium in both eyes and my optometrist says its from decades of reflection off the water. No one warned me. No ads. No school program. Just me and the ocean. Now I wear wraparounds but its too late. You think they care about surfers? Nah. They care about profits

mary lizardo

December 26, 2025 AT 06:54While the article presents a clinically accurate overview, it lacks critical engagement with the socioeconomic disparities in ophthalmic care. The assertion that surgery is ‘life-changing’ presupposes access, yet the global prevalence of untreated cases-particularly in low-resource regions-is not contextualized within colonial legacies of healthcare neglect. Furthermore, the uncritical endorsement of mitomycin C and amniotic membrane transplantation as ‘gold standards’ ignores the ethical implications of chemotherapeutic agents applied to non-malignant tissue. The tone, though authoritative, is dangerously reductive.

Alex Curran

December 27, 2025 AT 14:53Yeah mate I’ve seen this a hundred times down here. One bloke I know, fisherman in Port Lincoln, had it grow right over his pupil. Got the autograft done last year. No recurrence. But he still won’t wear his shades when he’s out on the boat. Says he’s ‘used to it’. Classic. The sun doesn’t take holidays. Neither should your eyes. Get the wraparounds. Seriously.

Chris Davidson

December 29, 2025 AT 10:22People think its just a bump. Its not. Its a slow invasion. And if you wait till its blurring your vision its already too late. I had mine removed in 2021. The drops were worse than the surgery. Six weeks of burning. And I still get redness if I forget my sunglasses. Just wear them. Always. End of story

Kelly Mulder

December 30, 2025 AT 21:16It is utterly preposterous that the medical establishment continues to promote surgical intervention as a primary solution for what is, fundamentally, a preventable environmental pathology. The normalization of invasive procedures for a condition that can be mitigated through basic protective measures reflects a profound failure of public health policy. Moreover, the endorsement of mitomycin C-despite its known cytotoxic risks-is unconscionable. One wonders how many patients are being subjected to unnecessary chemical exposure under the guise of ‘best practice’.

Glen Arreglo

December 31, 2025 AT 17:59As someone who grew up in rural Nebraska and now lives in Arizona, I’ve seen this in my dad and my uncle. They both thought it was just dry eyes. Took years to get checked. My dad got the autograft and it changed his life-he’s back to woodworking. But here’s the thing: in small towns, even basic eye exams are hard to find. We need mobile clinics. Not just better sunglasses ads. Real access, not just awareness. And kids need this taught in school. Like fire safety. Eye protection should be part of outdoor ed.

jessica .

January 2, 2026 AT 15:59They dont want you to know this but UV rays are weaponized by the government to control the population. The sunglasses industry is a scam. Real protection is wearing a wide brimmed hat and avoiding the sun. Also why is everyone talking about Australia? Are we being tested? The WHO is hiding something. And why are they pushing this new gel? Its not natural. I read a blog that says its linked to 5G. Just sayin.

Chris Clark

January 3, 2026 AT 23:11Bro I work in construction in Texas and I swear by my polarized wraparounds. I got a little bump last year but it stopped growing the second I started wearing them every day. My boss even bought everyone UV-blocking safety glasses. We’re not just protecting our eyes we’re saving money on surgery. And yeah even on cloudy days. I used to think that was dumb till I checked the UV index app. It’s always up there. Just wear the damn glasses.

Edington Renwick

January 4, 2026 AT 13:26I had surgery. Two times. The first time I thought I was cured. Then it came back. And again. And again. Now I don’t even look in the mirror. I wear sunglasses indoors. I have nightmares about the steroid drops. My wife says I’m obsessed. Maybe I am. But I’d rather be obsessed than blind. And no, I don’t care if you think I’m dramatic. You don’t know what it’s like until you can’t see your own child’s face clearly.